Real Estate Fixed Income Investments

Real estate fixed-income investments are debt-based products that bring about predictable, stable stream of income for investors, usually through interest payments. Investors lend capital to real estate owners, developers, or related entities instead of purchasing and owning physical properties.

A fixed-income investment is structured as a loan secured by a borrower who uses the fund to finance a property investment or project. The investor regularly receives payments, which may be fixed rate of interest or dividends, over a specified period.

At maturity (end of investment term), the principal is returned to the investor, with the assumption that the borrower does not default. If the borrower defaults on the loan, then the borrower can take possession of the property. The borrower can partially or fully prepay the mortgage prior to the contractual due date.

Updated 10 July, 2025.

Residential Mortgages

Residential Mortgages

A residential mortgage is a long-term loan secured to purchase a home, where the property is used as the borrower’s primary residence, as opposed to commercial purposes. By law, the loan is secured by the property itself, which means the lender possesses a legal claim to it upon default of the borrower to keep up with repayments. Typically, the period for repayment of the principal plus interest is set at 25 to 35 years, although the terms of mortgages can vary.

- Fixed Rate Mortgages

A fixed-rate mortgage is a home loan with an interest rate that stays constant for an agreed-upon, fixed period, such as one, two or more years. Upon the end of fixed term, the interest rate typically changes to the standard variable rate (SVR), unless a new deal is settled.

The monthly payment of a fixed-rate loan can be computed using the formula for the present value of a constant annuity with payment:

MP = MB x [i / (1 – (1+i)-n)]

Where:

MP = Constant monthly payment

MB = Mortgage balance or total amount borrowed

I = Monthly interest rate (defined as the stated annual rate divided by 12)

N = number of months in the term of the loan

Example:

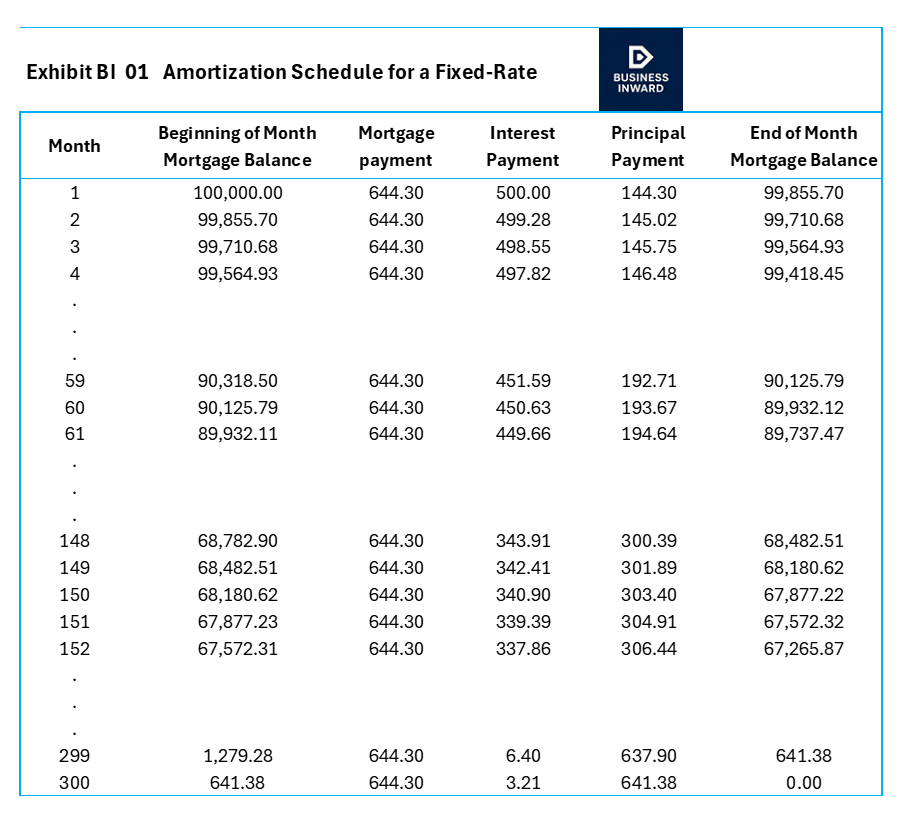

Johnson secured a loan of £100,000, 25-year mortgage (300 months), at a 6% annual nominal interest rate (a monthly interest rate of 0.5% (6%/12). The monthly payments for principal and interest.

Answer:

MP = £100,000 x [0.005/(1- (1.005)-300)] = £644.30

Interest-only & Variable-rate Mortgages

1. Interest-only Mortgages

Some mortgages are structured based on interest-only deals, meaning that the monthly payments are only interest payment for specified initial period. The two most broadly used interest-only loans are, first, the 30-year mortgage that commences with a 10-year interest-only period and is ensued by a 20-year fully amortizing period (known as 10/20 loan).

2. Variable-Rate Mortgages

A variable-or-adjustable-rate mortgage is a kind of loan where the monthly interest rate changes over the life (of the loan). These changes are typically associated with central bank rate, market and economic factors, which means that payments tend to fall or rise.

In view of Exhibit BI 01, the monthly mortgage payment that the borrower would have to make during the second year, for which a higher index rate of 8.5% applies, is equal to £903.36 (n=12 x 24 = 288, i = 10%/12, PV = +-£98,470.30, FV = £0, find PMT. Observe that the rise in interest rates between the first year and the second year has resulted in considerable rise (27.81%) in the monthly payment that the borrower is obliged to fulfil. The second-year balance equals £97,430.75, which is ascertained from the amortization, supposing no unscheduled principal payments: n = 12 x 23 = 276, i = 10%/12, PMT = £903.36, FV = £0.

Residential Mortgages & Default Risk

Residential Mortgages and Default Risk

Default risk is dispersion in economic outcomes owing to the actual or potential failure of a borrower to fulfil scheduled payments. For many residential mortgages, the full payment of the mortgage is backed by a public or private guarantee, in a way that mortgage investors are focused on interest-rate risk rather than default risk. Insured mortgage loans are, as a rule, extended dependent on an analysis of the underlying property and the creditworthiness of the borrower.

Creditworthiness analysis of the borrower and the safeguard provided to the lender by the underlying real estate asset is fundamental analysis that extensively depends substantially on ratio analysis. Ratios concerning the creditworthiness of the borrower oftentimes focus on the ratio between some measure of the borrower’s housing expenses to some measure of the borrower’s income. For instance, a debt-to-income ratio is estimated as the total housing expenses (comprising of principal, interest, taxes, and insurance) divided by the monthly income of the borrower, and it could be required to be more than a specified percentage for the borrower to qualify for mortgage insurance.

- Front-end or Housing Ratio

The front-end ratio (also Housing Expense Ratio) is the percentage of gross monthly income that goes toward your housing costs, which comprises of your mortgage payment, property taxes, mortgage insurance, and homeowner’s insurance.

- Formula for calculating Front-end Ratio:

Total Monthly Housing Expenses / Gross Monthly Income) x 100.

Lenders use front-end ratio to evaluate borrower’s ability to afford a mortgage. While specific threshold varies, lenders normally opt for a front-end ratio below 28%.

Formula Breakdown:

- Total Monthly Housing Expenses: This includes estimated monthly principal and interest payment (P&I), plus property taxes, homeowners insurance, and mortgage insurance (PMI), if applicable.

- Gross Monthly Income: This is total income before taxes and other deductions.

- Back-end or Total Debt-to-Income Ratio

The back-end ratio, or total debt-to-income (DTI) ratio, is a financial metric that estimates the percentage of a borrower’s gross monthly income that goes toward all monthly debt obligations, comprising of housing and non-housing debts.

Formula for calculating Back-end Ratio:

(Total Monthly Debt Payments / Gross Monthly Income) x 100.

Lenders use this ratio to evaluate a borrower’s risk and ability to manage their debt package.

The formula is: (Total Monthly Debt Payments / Gross Monthly Income) x 100 = Back-End Ratio.

Lenders use is ratio to assess a borrower’s risk and ability to manage their debt load.

Items that are included in total monthly debt payments:

- Housing expenses: Mortgage payments.

- Other debt payments: Payments for auto loans, student loans, personal loans, and other instalment loans.

- Revolving credit: Credit card payments.

- Other recurring debts: Such as alimony, child support, and lease payments.

Mortgage underwriters use the back-end ratio to ascertain a borrower’s ability to repay a loan. Lenders normally expect a back-end ratio of 36% or less, even as higher ratios may be acceptable in some circumstances.

Commercial Mortgages

1. Commercial Mortgages

A commercial mortgage is a loan obtained to purchase, develop, or refinance land or property for business purposes, secured by a legal charge on that non-residential property. Unlike residential mortgages, commercial mortgages are backed by real estate multi-family apartments, offices, shops, warehouses, retail and industrial properties, rather than owner-occupied residential properties. The core differences are its high deposit requirements, usually larger loan amounts, and less rigid, less regulated terms from lenders.

1.1 Covenants

As a rule, the covenants in a commercial mortgage are more elaborate than those in a corresponding residential loan agreement. Covenants are promises made by the borrower to the lender and oblige the borrower to maintain the property and sustain the fulfil specified financial conditions. Failure to fulfil the covenants can result in default and render the full loan amount due forth with.

1.2 Recourse

Recourse entails how the loan is secured, such as the potential capability of the lender to take possession of the property in the event of a default and the potential ability of the lender to pursue recovery from the borrower’s other assets. Lenders may insist on minimum deposit or balance to be kept in an account with them.

1.3 Cross-Collateral Provision

A cross-collateral provision, or cross-collateralization is a clause that provides for an asset pledged as collateral for one loan is used as security for a second loan from the same lender. This raises a lender’s security, as defaulting on any of the restricted loans permits them to take possession of the pledged asset to cover the outstanding debt. Such provisions are widely known in different financing types, namely credit-card mortgages, structured deals- potentially offering borrowers benefits (e.g., lower interest rates), while increasing the risk of losing assets in the event of default.

1.4 Loan-to-Value (LTV) Ratio

This ratio compares the mortgage amount to the appraised value of the property.

Key financial ratios for evaluating commercial mortgage default risk comprise of Loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, which estimates loan amount against property value. As with residential loans, the LTV ratio, both the origination of the loan and an ongoing basis, is a core measure used by lenders. The LTV is the ratio of the amount of the loan to the value (either market or appraised) of the property.

The LTV at which a lender will issue a loan varies depending on the lender, the property sector, and the geographic market in which the property is located, as well as the stage of the of the stage of the real estate cycle and other circumstances, such as the borrower’s creditworthiness.

This ratio compares the mortgage amount to the appraised value of the property

- LTV formula: Loan Balance / ( Deposit – property Value) = LTV Ratio

- High LTVs (above 80%) may be deemed high risk and could result in higher borrowing costs or a denial of the loan, as well as less equity in the property, which raises risk for the lender if property values fall.

- Impact on default risk: high LTV means less lender protection if property value falls.

- Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR)

The DSCR is a financial metric that estimates a company’s or property’s ability to cover its total debt obligations, as well as principal and interest payments, using its net operating income (NOI). A DSCR higher than 1.0 suggests adequate cash flow to meet these obligations, with higher ratios signaling lower risk to lenders and investors.

- Formula for DSCR: Net Operating Income / Total Debt Service = DSCR

- What the DSCR Disclose

- Solvency: It indicates if a borrower can consistently pay its debts from its earnings or the income generated by an asset.

- Risk Assessment: Lenders and investors use DCSR to measure the risk linked with lending money or investing in a project, as lower DSCR can indicate potential cash flow difficulty.

- Example: A property with an NOI of £550,000 and annual debt service of £350,000 has a DSCR of 1.83 (£550,000 / £300,000 = 1.83). This means that property generates £1.83 for every £1.00 of debt service.

- Ratio Interpretation:

- DSCR > 1.0: The company generates adequate income to cover its debt.

- DSCR < 1.0: The company does not generate adequate income to cover its debt obligations.

- Higher DSCR: suggests stronger financial health and lower risk for lenders.

- Low DSCR: Indicates the property is not generating adequate cash flow to service the debt, increasing the probability of default.

- Why These Ratios Are Important

- For Lenders: These ratios are fundamental tools for evaluating and managing the risk of commercial mortgage defaults, affecting loan approval decisions and allocation of capital.

- For Borrowers: Comprehending these ratios helps borrowers to understand their own financial position and be eligible for more favorable loan terms.

1.5 Interest Coverage Ratio (ICR)

In real estate, the interest coverage ratio (ICR) estimates a property’s or investor’s capability to cover its mortgage interest payments using its rental income, usually calculated as a percentage of ‘passing rental’ versus ‘finance costs’. Lenders use the ICR to evaluate risk and affordability for buy-to-let (BTL) mortgages, making sure that rental income can sustain the loan. For example, a common requirement is minimum ICR of 125%, signifying that the rental income must exceed the interest payment by 25%.

- Formula for Calculating Interest Coverage Ratio (ICR): (Annual Gross Rental Income / Annual Finance Costs) x 100 = ICR

OR

- Monthly Gross Rental Income / Monthly Finance Costs) x 100 = ICR

Why the ICR is Significant

- For Lenders: It is a vital risk management tool to make sure that borrower can meet debt obligations and that the property can guarantee the mortgage payments, even if interest rates increase.

- For Investors: It shows that the property’s financial robustness and ability to cushion (sustain) future expenses, such as property maintenance, taxes, and unexpected costs.

Characteristic ICR Requirements

- Lenders usually set a minimum ICR, such as 12%. This defines the gross rental income must be 25% higher than the mortgage interest payment.

- A higher ICR suggests a healthier financial position and lower risk for the lender.

1.6 Mortgage Stress Rate (MSR)

A mortgage stress rate is a hypothetical interest rate, higher the actual rate that lenders use to test if a borrowers can afford their repayments should interest rates increase. The MSR is used for Buy-to-Let (BTL) mortgages, to ensure that a borrower’s financial stability and decrease the lender’s risk.

How the Mortgage Stress Rate works:

- For Residential Mortgages

Lenders use a stress rate as part of an affordability test/check for borrowers taking out a mortgage with an initial rate fixed for less than five years. If rates increase unexpectedly, the lender realizes that the borrower can still comfortably meet their repayments. However, since 2022, it is no longer a compulsory requirement for UK residential mortgages, but many lenders still apply some form of stress testing.

- For Buy-to-Let (BTL) Mortgages

This measure is till critical and compulsory part of the affordability evaluation. The lender uses the stress rate to ascertain if the rental income from the property is adequate to cover the mortgage payments, encompassing a safety buffer, in case of future interest rate rises.

There is no specific “mortgage stress rate” formula, as the test is used in different ways, but a common method for buy-to-let mortgage is the “Stress Interest Coverage Ratio (SICR), computed as:

- SICR = (Rental Income /2) / (Loan Amount x Stress Rate / 2)

- Note: A specific percentage above the calculated interest, the Rental Cover ratio (between 125% and 145%), is required, which means the rental income must exceed the interest payment to pass the stress test.

Lease Financial Analysis

Decision to Lease or Buy

Financial lease analysis entails assessing the cost-effectiveness of a lease by computing the Net Present Value (NPV) of lease payments against buying an asset and analyzing the lease’s effect on a company’s financial statements. Under IFRS 16, most leases are recorded on the balance sheet as a right-of-use (ROU) asset and lease liability.

Financial analysis ascertains the lease’s financial viability by contrasting it against alternatives, evaluating the ROU asset and liability, and appraising the associated interest and expenses of depreciation.

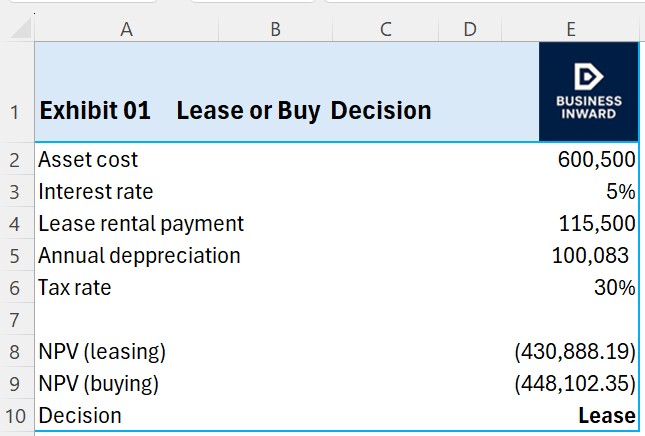

In this example, a firm has decided to acquire the use of a turbine costing £600,500. If acquired, the turbine will be depreciated on a straight-line basis to a residual value of zero. The turbine’s estimated life is 6 years, and the firm’s tax rate is 30%.

Spreadsheet Workings

Annual depreciation: £100,083<– =(E2-0)/6

NPV (Leasing): -£430,888.19 <– =PV(E3,6,E4*(1-E6),,1)

NPV (Buying): -£448,102.35 <– =-E2-PV(E3,6,E6*E5)

Decision: “Lease”<– =IF(A8>A9,”Lease”,”Buy”)

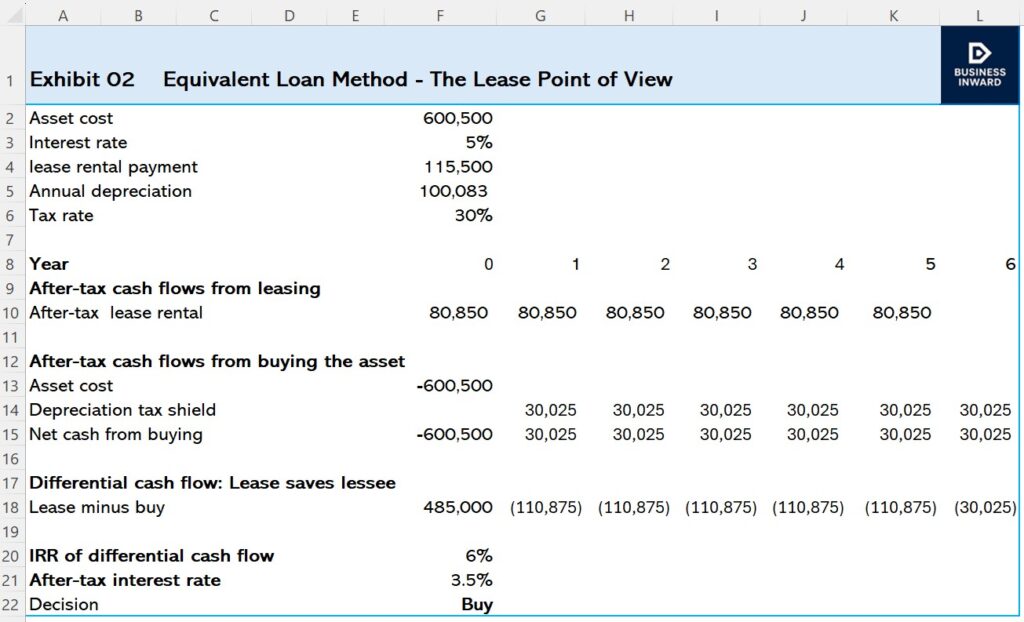

Equivalent Loan Method

In Exhibit 02 below, the rationale behind the equivalent-loan method is to create a hypothetical loan that is in some way equivalent to the lease. As such, it becomes easy to understand whether it is preferable to lease or buy.

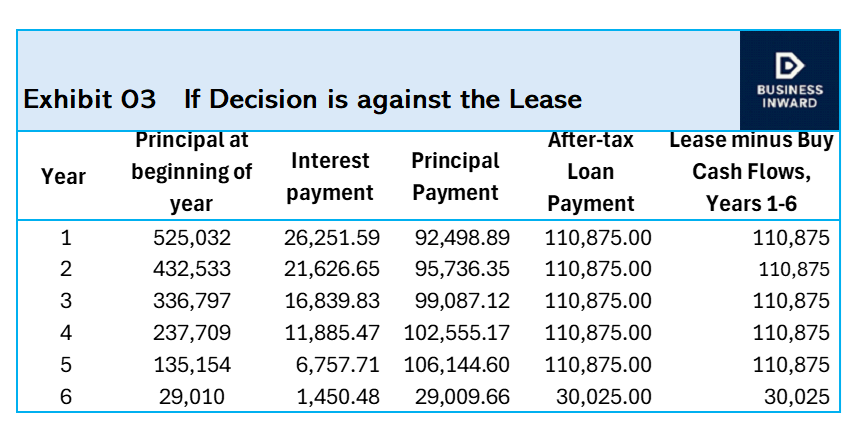

Exhibit 03 represents an alternative argument against a decision to lease. It appears that the firm can borrow 5% and also can borrow more money with the schedule of after-tax repayments whose outcome stemmed from the lease versus the buy.

The firm borrows £525,032 from a financial institution. At the end of the year, the firm repays £118,750.48 to the financial institution, of which £26,498.89 is interest and remainder, £92,498.89, is repayment of principal.

At the beginning of year 6, there still £29,010 of principal outstanding; which is fully paid off at the end of the year with an after-tax payment of £30,025. If the firm considering leasing the asset so as to get financing of £485,000, which the lease gives, it should instead borrow £525,032 from the financial at 5%.